More Food for Thought…

by: Janet McCabe and Kim Akass

Artie Bucco is having a bad episode (“Luxury Lounge”, 6: 7). Business at Vesuvio is floundering: the restaurant is almost deserted, apart from Benny hitting on new hostess Martina, American Express fraud investigators are asking uncomfortable questions about stolen customer credit card numbers, Amex cancel their services until the matter is resolved, Artie has a meltdown, accusing staff of stealing from him, everyone is raving about the food at Da Giovanni’s and there are mutterings that Artie’s cuisine is not what it was.

Apologies for coming late to the table, but season 6 of The Sopranos is only just airing here in the UK. Dana Polan eloquently wrote about Tony and Carmela’s obsession with sushi back in April. Devouring the hottest food fad our urban, upscale couple dine at their favourite sushi restaurant, Noh. Tempted by tempuras, and greedy for gyoza, furore over futomaki ignites the latest rift in the Soprano marriage. Gone are the days of Tony’s philandering with goomahs. Nowadays he plays away from home with some raw sexy sashimi.

All this ends with Tony’s near fatal shooting. No more talk of sushi as the mobster boss hovers between life and death, apparently somewhere between a New Jersey hospital bed and a hotel bar in Orange County, California.

Relatives, friends and the crew gather round. Pizza and Rigatoni become the plat-du-jour. No getting away from it. In times of family crisis raw fish is no substitute for a dish of steaming home-baked ziti. Melancholia descends over the text; symptoms of trauma permeate the narrative; and nostalgia, a desire to return to the old ways, pervades the series.

Tony’s near death experience, in fact, becomes the founding trauma for season 6 reminding us that all things must end. Even though we know this show will not be over until the fat man sings, his brush with death traumatizes the text.

E. Ann Kaplan, extending Sigmund Freud’s theories on trauma, and including his problematic treaty Moses and Monotheism, argues that at certain historical moments particular aesthetic forms emerge ‘to accommodate fears and fantasies related to suppressed historical events’ (E Ann Kaplan, ‘Melodrama, Cinema and Trauma,’ Screen 42: 2 Summer 200: 203). Focusing on melodrama, and understanding this generic formation as repeating the traumas of both class and gender struggle, she argues that ‘melodrama would, in its very generic formation, constitute a traumatic cultural symptom … [and that] taken up by cinema, it arguably continued to repeat, while concealing cultural traumas too painful to confront directly (ibid). In this context, it is reasonable to associate melodrama, as an aesthetic form, with the dissociated traumas of a post-9/11 America, the mobster world disintegrating – a television series ending and a network in crisis.

Which returns us to Artie Bucco.

Long have we known the restaurateur as prone to melodramatic outbursts. His passion for pasta is as famed as his emotional eruptions. With Artie there is always a simmering rage bubbling just beneath the surface, ready to spill over at the slightest provocation. Never has a restaurant been so aptly named. Inexplicable anger, random bouts of brutal violence and inappropriate behaviour; Artie is and about displacement. Could it not therefore be argued that Artie – his body, his food, his restaurant – suffers melancholia, a traumatic symptom of the series’ elegiac sense of loss – of the old ways, of respect, of honour, of family, of home. No wonder Tony always looks out for his old friend and returns week after week to eat.

Vesuvio resembles a sepia photograph, muted browns and hues. It is the mise-en-scene of nostalgia, its walls are covered with romantic renderings of the old country, the music evokes the Italian soul, it is the place where people come to comfort eat and be with family. But, at the beginning of ‘Luxury Lounge’ Tony hosts a banquet at the restaurant to welcome in the ‘new blood’ (Gerry Turciano and Burt Gervasi). Celebrations are marred by complaints that the food is slow in coming; and there are mutterings that Artie is off his game. Long gone are the days of Adriana greeting guests. (Never could you imagine her disrespecting Artie.) Now Mexicans cook the food and the Eastern European hostess trades credit card numbers to buy $600 sandals – things are not what they used to be.

Is it possible that we are witness to the breakdown of the old order – the mob preferring to eat nouvelle Italian cuisine at Da Giavanni’s because Vesuvio, like the menu, is looking tired. This episode, to us at least, brings into focus the impact of the near loss of Tony. Hits are being farmed out to Italians who are eager to tour Ground Zero and take advantage of the weak dollar; small time crooks like Benny are disrespecting the old ways of doing business; Christopher while being primed to take over as boss is far more interested in the glamour of taking the helm of a Hollywood gangster movie than actual mob management. (You can never imagine Tony Soprano knocking down Humphrey Bogart’s widow for a $30,000 gift basket. Is there no respect for a class act?)

Enough already. Tony takes matters in hand. His failed attempt to intervene in the dispute with Benny results in the chef’s hand being plunged into boiling spaghetti sauce and shedding its skin ‘like a glove’. Bruised and battered, Artie is comforted by Tony. But it is time for tough love. And here we are given insight into why Tony protects Artie. ‘On one of the bleakest nights of my life. After all the shit with my mother. And the terrible storm. I came here with Carm and the kids. We ate. We drank. And we were happy.’ Not only does he evoke the significance of Vesuvio as a place of healing, as somewhere the ‘family’ comes together to reaffirm itself. But it is also a self-reflective moment, a nostalgic reminder in the final season of what has passed. A sense of melancholia descends for times gone. Tony may well recognise that the playing field of business changes, but he returns to eat as he recovers from his near-fatal shooting. After all Artie is the only one who will prepare the bland medicinal food needed for his recuperation. Yet his insistence that Artie stops bothering the customers with his corny jokes (echoing Charmaine’s advice earlier) and to get back in the kitchen betrays a textual unease over change.

But Artie does not hear him.

Still at episode end, Artie’s actions tell a different story. Alone in the kitchen he is doing the accounts, his hand bandaged, his face battered, he is licking his wounds from the episode – in Tony’s words ‘wearing his pity’. He is the literal physical embodiment of suffering but he also carries the burden of narrative trauma. Charmaine enters the kitchen. They have customers. ‘The kitchen is closed,’ Artie says. ‘The bottle is already open,’ Charmaine retorts. ‘They’ll eat what I give them,’ says the person the NJ Zagat calls the ‘warm and convivial host’.

Pulling out a tray of skinned rabbit from the fridge. Retrieving the old and well-thumbed family recipe book. Caressing the notebook lovingly, his fingers lingering over his grandfather’s name barely legible on the cover. Stained with good chianti, olive oil and experience. Flicking through the pages, finding the recipe (in Italian of course) before pulling ingredients from the fridge. Despite Charmaine’s warning that not everyone likes it –

Artie will cook rabbit. Lovingly he prepares the dish: the old way.

The hauntingly evocative music strikes up ‘Recuerdos de la Alhambra’ as Artie lights the gas, throws garlic in the pan and enjoys the heavy aromas of his grandfather’s recipe. Meanwhile the Italian hit men head home, comparing the gifts they have purchased for their families. Cutting between the two scenes reminds us that food is more than sustenance. It is about tradition. It is about a longer history of Italian immigration trafficking across the Atlantic. It is about a series that has enriched a network.

Cherished family recipes give voice to what cannot be said; and Artie speaks its complex language. Just as the music borders on sadness, on loss, on the inevitability of time passing, it at the same time, and like the food, is tender and comforting. The violence sustained on Artie’s body may betray trauma, but these images seal over the ruptures caused by Tony’s near death experience and the knowledge that the series must end. It harks back to the past as it hints at continuity. Such a healing moment reassures us that all will be well as long as Artie is in the kitchen.

Image Credits:

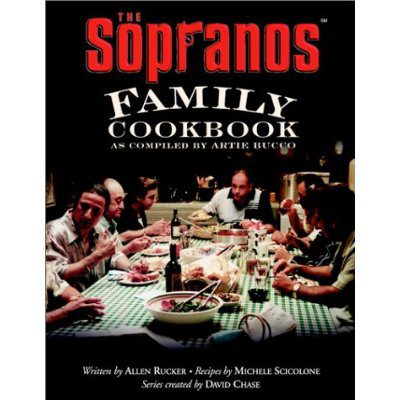

1.The Sopranos

2. Family Cookbook

Please feel free to comment.