TV Legal Drama Speaks to U.S. Citizens

by: Mary Beth Haralovich / University of Arizona

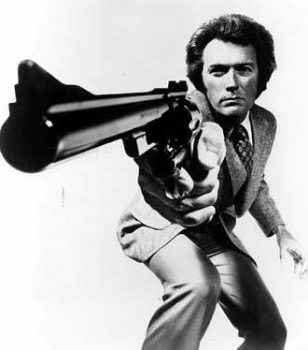

Clint Eastwood in Dirty Harry

In the early 1970s, Dirty Harry famously took on the issue of constitutional rights for US citizens suspected of crimes. Clint Eastwood’s cop movie launched the popular narrative enigma that would influence decades of television legal drama: “the fruit of the poisoned tree.” Evidence obtained in an illegal search is considered “poisoned” and not admissible in court. Although relevant to only a small number of cases in real life, in television legal drama “inadmissible evidence” guarantees drama, nurtures performance and invites the TV audience to share in fear, victimization and social injustice caused by the Constitution. Today, constitutional rights have been scaled back through the USA Patriot Act. Adopted 45 days after 9/11, the Patriot Act grants government temporary permission to circumvent the constitutional rights of US citizens in the fight against terrorism. Although it has not (yet) had the TV dramatic reach of the 1960s Miranda decision, the Patriot Act is finding its way into television entertainment.

Television stories about “fruit of the poisoned tree” and the Patriot Act is entertainment that calls upon the verisimilitude of contemporary politics. Television presents constitutional rights through the conventions of entertainment — performance, aesthetics, character interactions. Characters in TV legal drama are inscribed with social meanings. The city cop is working class, beefy and rough; his job to protect and serve is hampered by the rights of citizens. The federal cop is more polished, better educated, better dressed and more powerful. Lawyers and judges are educated legal minds who explain issues to both diegetic characters and the TV audience. Guilty criminals and their lawyers are smug in the knowledge that they can turn the system to their advantage and continue to endanger an innocent public. There is the social subject that Thomas Elsaesser has called, in reference to 1930s Warner Bros. bio-pics, the “civic audience” — the TV audience and our diegetic surrogates, addressed as citizens. “Ripped from today’s headlines,” TV legal drama is more like docudrama than fiction, as the contending forces of constitutional rights and public safety are worked through TV legal drama for the civic audience.

Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel described Harry Callahan as “Archie Bunker with a gun,” evoking the political and generational divide of the 1960s and 1970s. In Miranda: The Story of America’s Right to Remain Silent, attorney Gary L. Stuart situates the Miranda decision and its underlying racial and class assumptions in the social context of the US in the 1960s. Stuart argues that prior to Miranda, Americans of a particular class would have understood that they have the right to remain silent, whether inside the courtroom or in a police interrogation room. For white, middle-class and educated citizens, this right did not have to be articulated. Stuart shows how social change in the United States after World War II began to “question some deep-rooted assumptions about race, about gender, and about law.” He identifies two primary areas for change: (1) the desire for greater social and economic equity, seen in the movements for civil rights and women’s rights; and (2) the availability of higher education for children of the lower- and middle-classes.

These children went to college and entered professions that were traditionally the province of the upper class — in particular law and academe. Now empowered, these educated formerly lower-class citizens pushed for egalitarian reforms. Among these reforms was the right to an attorney. The state assumed responsibility for providing legal counsel for citizens who could not afford it. However, the suspect had to invoke the right to counsel (Stuart, xv-xvi). Before Miranda, the state was not obligated to inform the suspect that s/he had the right to counsel.

In March 1963, Phoenix police arrested a young, poor and uneducated Hispanic man, Ernesto Miranda, who confessed to the crime during interrogation. Stuart explains the psychological importance of confession in police procedure: “confess, and all will be forgiven — that is what the police interrogator conveys to the suspect … in truth [,] the suspect will be forgiven by the cop … for the higher authority, however … the wrongdoer must pay for what he did” (Stuart xv). Ernesto Miranda’s conviction rested almost entirely on his self-incriminating confession. Stuart describes Miranda as “an uneducated, ethnically disenfranchised citizen with virtually no voice to defend himself.” Miranda was guilty, but the Supreme Court found that “the law must step forward … to provide him with legal protection to which all innocent American citizens can lay claim” (xvii). Thus, constitutional protections apply equally to the innocent and the guilty, to the educated and the uneducated.

The Miranda decision was a safeguard against police abuse and coerced confessions. Stuart explains its impact on the conduct of criminal investigations: “police interrogation techniques were developed [and] specifically designed to induce suspects into unknowingly giving up their Fifth and Sixth Amendment rights” (xviii) [Fifth is right to remain silent; Sixth is right to representation]. The Miranda decision affected police procedure and the conduct of investigations. Scenes of confession, interrogation, and evidence lie at the heart of television legal drama. Educated, articulate legal minds are positioned against frustrated working cops who have to revise their procedures in order to obey the law. This opposition grows directly out of the post-WWII social context of the Miranda decision that Stuart describes: thinker v. doer, mind v. body, legal thought v. life on the street, Archie Bunker v. Meathead.

In Dirty Harry, the Constitution protects the rights of a particularly heinous criminal, Scorpio, a serial killer-rapist. In the Kezar Stadium sequence, Harry tortures Scorpio during the arrest. Through editing and shot scale, this scene establishes the parallel intensity and psychotic states of the cop and the criminal. Out in the street, Harry has the gaze of power and ability to protect public safety. Then, Harry is called into the DA’s office where he and the civic audience learn that Scorpio will go free. In the DA’s office, Harry does not relinquish the gaze of power he had at Kezar Stadium, but he tinges it with insubordination and frustration. The film argues that cops cannot work effectively within the procedures required of the police by law.

Dirty Harry distinguishes between justice and law. The law states that the rights of the accused are more important than the criminal’s obvious guilt. Justice tells us the law is too lenient; it’s crazy. The cop enunciates the dangers to public safety: “who speaks for her?” The lawyers make speeches, reasoned and dispassionate readings that explain the law in arcane ways, as if the law is based in knowledge that the untutored person cannot fully access. The cop’s words and gestures are succinct. It’s the famous Eastwood performance.

Dennis Franz in NYPD Blue

Twenty years later in 1993, NYPD Blue burst onto television screens as R-rated television, for language, sexual situations and nudity. The first scene of the first episode of NYPD Blue takes on constitutional rights with the now-familiar cast of characters: cops, DA, smug perpetrators and their lawyer, and the civic audience. In 1993, we don’t need lengthy speeches to explain constitutional provisions; “inadmissible evidence” has become a convention of television legal drama and police procedure. However, what we do need (as viewers of this new and startling television series) is a position on Andy Sipowicz, the cop who violates rights. This is important for the stability of the series and to establish sympathy for its continuing characters. Andy is another “Archie Bunker with a gun,” but his physical presence is different from Harry’s. Andy is inarticulate and beefy; he squirms on the stand. Andy is the comic side of Archie Bunker’s working-class conservatism.

Like Harry, Andy is entertainment. NYPD Blue starts with energy, in the courtroom and in its aftermath. The scene and the show move quickly. Andy’s partner, John Kelly (David Caruso) provides us as to how the civic audience could perceive Andy. Kelly laughs and enjoys watching Sipowicz on the stand. Andy is not a guy you love to hate; he’s a guy you love to like.

Eastwood’s subtle Dirty Harry performance (gestures, eyebrows, curling lips, squinting eyes) becomes in NYPD Blue the broader gestures of Andy’s bull-in-the-china-shop and his verbal assault on the District Attorney. NYPD Blue aligns entertainment (action, shocking sexual language and gesture, visceral frustration) with the working class cop. There is energy in Dennis Franz’s performance and the show’s editing. We need no thoughtful elaborate speeches to present the issues of rights. NYPD Blue‘s first scene invites the TV audience to be entertained and enjoy the characters even as the civic audience watches as criminals go free.

Fast forward to today, to the Patriot Act on TV legal drama. Enunciation and performance have shifted. The cop is federal, an enforcer with the sure gaze of power. Rights and privacy stand in the way of public safety. In the “fruit of the poisoned tree” scenario, the educated professional represents the law that frustrates the police. In the Patriot Act scenario, the educated professional surrenders to the war on terrorism. The Patriot Act is not enunciated with antic energy or the entertainment value of cops working against the system. The tone of performance is different. It’s dire and serious. Two recent examples are Without a Trace and The 4400.

In Without a Trace, the FBI seeks evidence that will help them track a missing child, taken by a pedophile. Agents visit the office of a social worker who protects the privacy of her clients. The agent uses the Patriot Act instead of a search warrant. The time to obtain a warrant would get in the way of the investigation, slow it down. Without a Trace uses a narrative and stylistic device to establish the importance of time. As hours pass, the likelihood of finding the missing person diminishes quickly. Thus, urgency and suspense derive from both narrative and verisimilar motivations. Pressured by time, the young affable agent exerts his power with friendliness. The social worker succumbs immediately. She recognizes that patriotism and terrorism have overcome constitutional protections of privacy. Even though she surrenders willingly, the narrative exacts a punishment. The pedophile whose rights she was protecting has kidnapped her child.

The Patriot Act in The 4400 is not as friendly. In this limited run series about people who were taken by aliens, 4400 are returned to earth in a mass landing. Homeland Security is involved in the investigation and decisions about how to handle these former captives. The patriarchal voice of the Patriot Act and Homeland Security suppress investigative journalism in the interest of national security and public safety. The local chief of Homeland Security advises television news producers to stop covering the story. In a visual face off, the power of Home Sec meets the weak TV news producer.

Cast of Without a Trace

Some TV legal drama interpolates the civic audience not as powerless onlookers but with invitations to think. Here, public safety derives from principles and rights, not from enforcement. The courtroom is a venue to present civic lessons. The courtroom drama suspends verisimilitude to explore issues. Compelling speeches, well-delivered, combine intellectual and emotional aspects of the law, using the pathos of melodrama to describe issues and our stakes in them. There are numerous examples. On Boston Legal, Rev. Al Sharpton walks into a courtroom and makes a speech about civil rights. He is not a character in the drama; he appears as the Rev. Al Sharpton, activist. Although the judge admonishes Sharpton that he has no standing to address the court, Sharpton delivers his speech anyway.

The Practice takes on the Patriot Act provision that allows government to limit political protest to a “free speech zone.” On Law and Order, an Iraqi-American woman has killed a female US soldier who tortured her brother at Abu Graib. In the courtroom, the attorneys explore whether a US citizen can be treated as a prisoner of war.

Constitutional rights and public safety are contending forces in TV legal drama. When the genre stabilizes around police procedure, the tendency is to stress the dangers that rights present to public safety. When the genre stabilizes around federal authority, cops have more formal power. In the courtroom, smart attorneys interpret the law and present positions. The constitution provides verisimilitude as the principles of US democracy play out week after week in various guises. In all of its iterations, TV legal drama has a didactic function that is fundamental to the genre. For the last word, let’s turn to Barry Levinson (Homicide: Life on the Street and Oz). He produced and played a judge in the short-lived 2004 series, The Jury. Each episode of this show was like Twelve Angry Men, but without the central heroic character. The Jury followed the deliberations of ordinary people as they reviewed evidence and came to an opinion about a case. In an ironic moment, the judge/producer vents his frustration with a jury that wants a mistrial and blames television.

Works Cited

Thomas Elsaesser, “Film History as Social History: The Dieterle/Warner Brothers Bio-pic,” Wide Angle 8:2 (1986).

Gary L. Stuart, Miranda: The Story of America’s Right to Remain Silent. Tucson: U of Arizona P, 2004.

Image Credits:

1. Clint Eastwood in Dirty Harry

Links of Interest:

USA Patriot Act

Miranda Rights

Department of Homeland Security

Dirty Harry

NYPD Blue official site

Without a Trace official site

The 4400 official site

Boston Legal official site

The Jury website

Please feel free to comment.

I would venture that most of us haven’t read the Patriot Act, or, for that matter, most of the laws and policies we are so familiar with. How do we know that we have the right to remain silent, or that we can get immunity for ratting out our partner in crime? –Probably not from 9th grade civics. So much of what we know and understand about the judicial process comes from television, and I’m not talking about C-SPAN. But what’s at stake here? Sure, legal procedurals are very popular, and they can be commended for broaching topics and exposing issues not touched by most other shows (or often by the media in general). Still, narrative closure is paramount, and the shows often focus on the individuals operating within (or without of) the system, rather than the system itself. Instead of being challenged, we are mostly reassured. Is it the case that we don’t really have to consider our legal system and judicial process because TV will do it for us?

perhaps you change the title to “. . .speaks to white US citizens.”

Pingback: FlowTV | Teaching Television, or What I’ve Learned From Flow